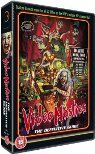

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Video Nasties: The Definitive Guide (2010) Film Review

The discs that make up Video Nasties: The Definitive Guide are, like Nucleus Films' previous two volumes of Grindhouse Trailer Classics, a painstakingly curated trailer reel that pays affectionate if sometimes wry tribute to a bygone chapter in the history of genre cinema – except that the 72 trailers collected here are altogether more comprehensive, including each and every title that ever found its way onto the list of so-called 'video nasties' banned in the early Eighties by the Director of Public Prosecutions on the grounds that they were "obscene" and likely to "deprave and corrupt" viewers.

These trailers have been lovingly compiled by Nucleus' co-founder Marc Morris who, as co-author of the books Art Of The Nasty (2009) and Shock! Horror!: Astounding Artwork Form The Video Nasty Era (2005), has also ensured that copies of all the titles' sensational VHS cover art are presented in extensive galleries. There is even, on disc three, an exhaustive 53-minute compilation of the different video idents from the period, as vivid testimony to the sheer number of independent fly-by-night operations that proliferated in the 'pre-certificate' period of 1979 to 1984 (before the Video Recordings Act required that all releases for the home market from then on be vetted and classified by the BBFC).

Disc one offers trailers for the 39 titles that were successfully prosecuted by the DPP, while Disc Two has the trailers for a further 33 titles that were initially banned, but subsequently acquitted and removed from the list. It is possible to watch these in an uninterrupted trailer show – but it is far better to view the trailers with their newly filmed introductions from a series of talking heads including media academics (Julian Petley, Patricia MacCormack, Xavier Mendik), and genre journalists (Kim Newman, Alan Jones, Emily Booth, Stephen Thrower, Allan Bryce, Brad Stevens and Marc Morris himself), as well as the occasional comment from filmmakers Ruggero Deodato (Cannibal Holocaust, The House On The Edge Of The Park) and Chris Smith (Creep, Severance, Triangle).

These introductions vary as much as the trailers that they preface, but are almost all interesting and witty, contextualising, sometimes even analysing, the films while either ridiculing or passionately championing them, and speculating (often with great bafflement) as to why they might have been banned in the first place.

Some were evidently added to the list more for their lurid titles or straplines than for their relatively innocuous content, with the appearance of certain keywords in the title ("cannibal", "don't", "experiment" or any reference to a tool) virtually guaranteeing a ban purely by association. Likewise Tobe Hooper's "almost completely uncontroversial" Death Trap and his later The Funhouse evidently found their way onto the list merely because of the notoriety of the same director's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, even if the latter was itself never an official video nasty.

Kim Newman stresses the "luck of the draw" that saw some slashers (The Burning, Don't Go In The Woods, Frozen Scream, Pranks) outlawed and others left alone even when there was little discernible difference in their content. Contributors seem genuinely puzzled as to how bans could ever have been slapped on titles like Anthropophagus The Beast, The Beast In Heat ("pure concentrated camp"), Blood Feast ("it's just hilarious"), Tenebrae (which had in fact been passed by the BBFC for theatrical release), Contamination (recently rereleased uncut with a 15 certificate), Inferno ("probably one of the most lunatic additions to the video nasty list") and Terror Eyes ("it got a theatrical release in Britain").

No one, on the other hand, steps forward to defend the use of actual animal cruelty in Italian exploitation films (although Julian Petley comes close in his discussion of authenticating effects in Deodato's Cannibal Holocaust). Morris concedes that the mondo extremity of Faces Of Death is "stomach-churning" and should be approached with "extreme caution". Alan Jones openly refers to those who worked for the Director of Public Prosecutions as "idiots", but he does, with typical dryness, approve their decision to proscribe Late Night Trains - "mainly because of the awful Demis Roussos theme song."

Everything comes together in a feature-length documentary on disc three, Jake West's Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship And Videotape. This thoroughly researched and well-made featurette traces how the unprecedented freedoms in film viewing brought about by the home video revolution of the early Eighties soon led to an irrational and ill-informed backlash by the press, religious campaigning groups and politicians, until eventually the long list of video nasties was banned and a system of compulsory classification for videos was established, changing forever the shape of film distribution and access in the UK.

Hilariously opening with a rapid, context-free montage of the nastiest scenes from each and every banned title (like the previous two discs on methamphetamines), West's film defies its viewers to be corrupted and depraved by this sensational parade of Grand Guignol, before presenting the historical context, reception and influence of these films and their distribution, and exposing the motivations behind their banning as at best small-minded patrician stupidity and at worst a Thatcherite conspiracy to distract from governmental inadequacies, erode civil liberties and strip away judicial powers.

Alongside carefully collated file footage and clippings from the times, there are new interviews with academics, critics and filmmakers who line up now (as very few did then) to pour public scorn on the banning decisions, while Sir Graham Bright (who introduced the Video Recordings Act 1984) and Peter Kruger (former operational head of the Obscene Publications Squad) step forward, gamely yet lamely, to defend their past (and abiding) censure of these 72 supposedly "evil" movies. The issues with which West's film deals are serious, but his light touch and expert use of dialectic juxtapositions ensure that Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship and Videotape is also never less than entertaining.

The film's real hero turns out to be Martin Barker, an academic who in 1984 seemed a lone voice in his public opposition to all the censorship and assaults on freedom, and who was greatly vilified for his efforts at the time. What a contrast, then, in the hearty applause that met his appearance on-stage after the documentary's world premiere at FrightFest 2010.

The same horror festival was also forced by Westminster Council to show a BBFC-cut version of the remake of I Spit On Your Grave (one of the most notorious of the original video nasties) and to withdraw altogether from screening a heavily mutilated version of controversial state-of-the-nation shocker A Serbian Film - all of which suggests that the era of censorious hysteria commemorated by Marc Morris' excellent three-disc set may not quite yet have been confined to the annals of ancient history.

Reviewed on: 09 Nov 2010If you like this, try:

Resurrecting The Street WalkerA Serbian Film

Slice And Dice: The Slasher Film Forever